Meander 3: Adventures in democracy

No river can run in a straight line longer than ten times its width, even in a flat valley. If the river is fifty feet wide, it will stray from its course in five hundred feet or less. This is due to shifting sediment accumulation along the river's path, causing variable current speeds. When the currents become strong enough to eat into the banks in some areas, the river begins to meander.

Meander No. 3: Adventures in Democracy

As a child growing up in the former Yugoslavia in the 1960's, I did not like political hacks who got a kick out of showing off their power. I was utterly bored by politicians talking for hours without caring about what we, the children, had to endure. Didn't they know what truly mattered?! These curmudgeons - these serial complainers - had no humor or patience for dissenting opinions like mine. There was no room in their lives for beauty and small miracles. I abhorred violence. I did not like ugliness. I knew, even at a young age, that none of these qualities were a way forward, and I rebelled.

And though my list of grievances grew long, I was not without self-criticism, and so too grew frustration with myself. I realized that I was beginning to sound like one of those cynics.

It was at this moment that I decided to do something about my discontent. It was time to go on a journey, and I needed to meander.

Perhaps as a result of growing up in Yugoslavia, I was in awe of the spirit of democracy in the United States. From afar, I marveled at the idea that people could come together and create shared plans for the future. I adored Buster Keaton and his movies celebrating the journey from colossal failure to smashing success. I liked Buster's ability to turn a disaster into a solution. I was enchanted by Black Elk Speaks, which reminded me of the power of community rituals. I read Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and wished my leaders would be equally wise and succinct. I cheered for Martin Luther King's commitment to making change through non-violence.

Most profoundly, I was enchanted by American music. I still remember discovering the recording of Benny Goodman's 1938 concert at Carnegie Hall. The music was a revelation, a gift, a metaphor for what the world might be. I wrote about this before. The Cold War pitted the West's focus on individual freedom and liberty against the East's collectivism. But here was an art form that beautifully combined individual and collective achievements. Musicians play together, as a collective, and then veer off to showcase their own virtuosity. They may 'meander', and that's fully encouraged, as long as they bring it back. Of course, everyone had to know their stuff. Taking a solo was an earned reward for their talent and mastery. And the bandleader was a facilitator who helped foster greatness in others, even if it meant taking a back seat.

My first experience with American Culture came from my early record shop discoveries: starting with Benny Goodman: Live at Carnegie Hall

I imagined society as a jazz band: the collective agrees on an issue, and then talented 'soloists' showcase their unique skills in displays of virtuosity that imbue the collective with personal insight and expertise. This idea gave me hope and excitement. I was as certain then as I am now that such a model is the only way to create "collaborative democracy," which is the only viable path forward for us all.

When I immigrated to the United States in the 1970s, all of this (including my reverence for American democracy) was put to the test in public meetings. The first meeting I attended addressed improving the safety of bicyclists and drivers on a dangerous stretch of road. I happened to use the route for bicycle commuting, and I could personally attest to its perilousness. I was eager to see democracy in action. How would these community members shape the solution?

It quickly became apparent that people living along that road opposed any improvements. They saw bicyclists as an inconvenient nuisance. But they didn't have the courage to come out and say that. Instead, they talked about “preserving their community's character" and argued that if the city widened the existing two-lane road now, what would prevent it from widening it further in the future? Over the objections of the bicyclists, who were in the minority, they decided that no shoulder was needed. Now, more than 30 years later, the road remains the same.

Bike lanes, so common around the world, are still met with resistance.

What happened? I saw community power at work, but that power rested only on the ability of residents to oppose change. Surely this meeting was an exception, right?

But after attending other public meetings, I noticed the same patterns. People complained about government intrusion and the tax increase needed to support an extravagant hobby like bicycling or affordable housing. Some spoke at great length, their chance at Filibuster, and the bulk of these meetings consisted of individuals who spoke loudly and forever, intimidating others. They threatened legal action if their ideas were to be ignored. I heard a lot of complaining but no new ideas on viable solutions. In short, a few cranky people dominated the proceedings, and I was reminded of those I rebelled against in Yugoslavia, here disguised as ordinary citizens.

I left these meetings disappointed, but it started me thinking... Could an immigrant like myself (my wife called me "imported") use idealism and innocence - my beginner's mind - to improve public meetings? Perhaps, with my fresh eyes, I would see opportunities missed by others. Did I dare to question? To suggest that the cogs of our democracy could use a little oil?

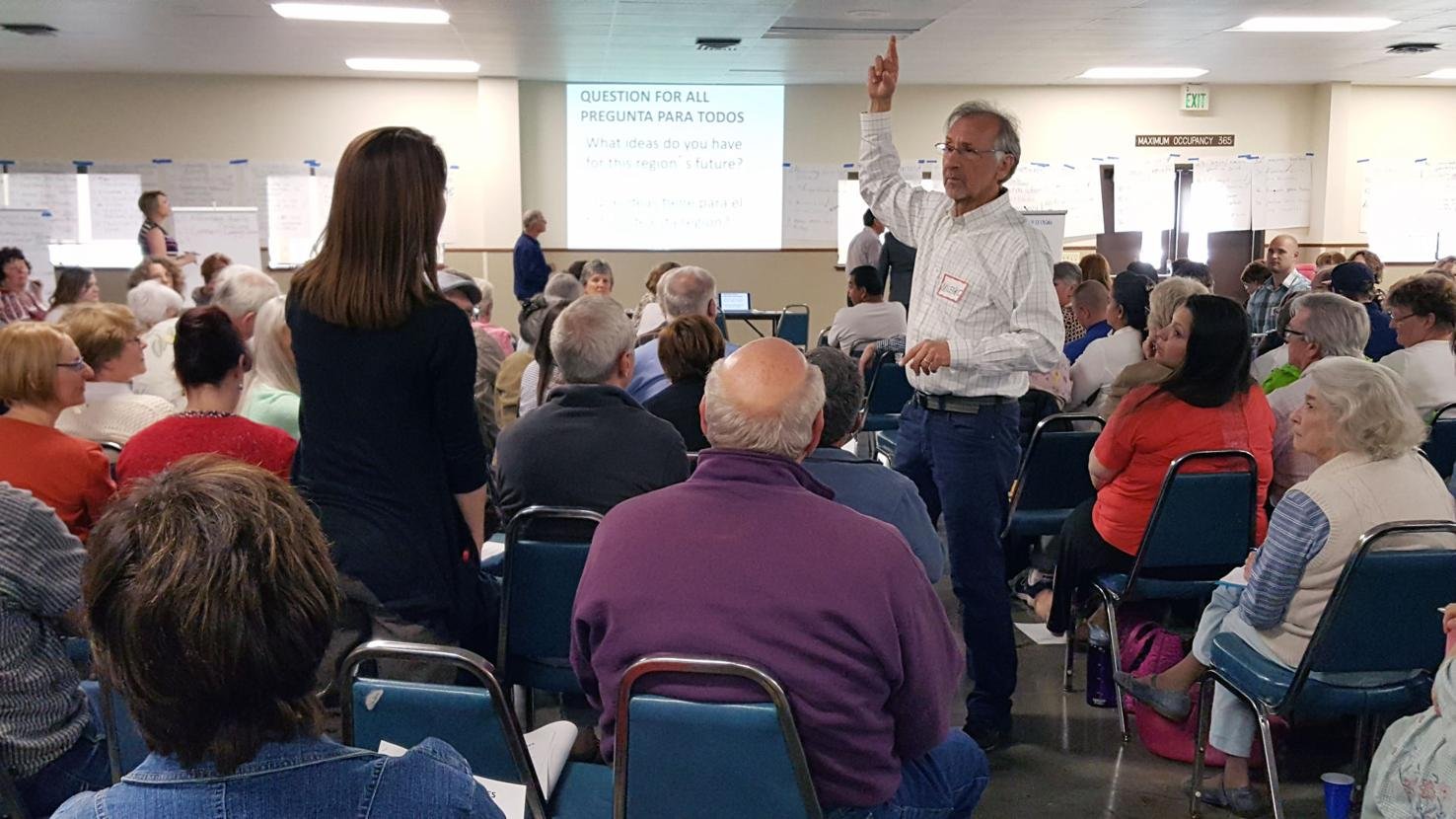

It was a gutsy call, and, in 1986, I founded a nonprofit called Pomegranate Center to explore how people can turn their differences into insights. I knew next to nothing about fundraising, bylaws, Boards of Directors, or strategic planning. However, Pomegranate Center was going to uphold a set of principles: address current needs and sustain future generations; combine the insights of many disciplines and ways of thinking; encourage positive dialogue; bring forward diverse voices; learn and educate by doing-hands-on projects that turn complex ideas into manageable tasks; stretch beyond the limits of conventional thinking, and allow for spontaneity and humor. It was my hope that these principles would counteract the negative habits that I'd seen at community meetings.

Were my hopes well-placed? Or was I too idealistic? In a future Meander installment, I will explain the critical lessons from practicing these principles.